"Nothing is permanent, except change"

|

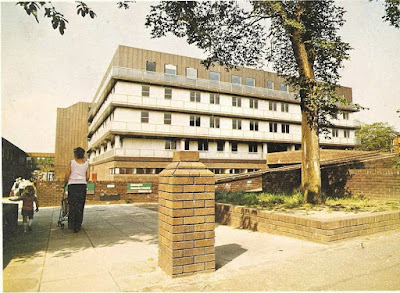

| Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, with the debris of the Southern General's Nightingale wards in front of it |

Glasgow Hospitals - gone, but not forgotten

I have written here about the Glasgow Poorhouses, several of which evolved into hospitals over time. This included the Town's Hospital, Stobhill Hospital, Woodilee Hospital, the Southern General Hospital, Oakbank Hospital and Duke Street Hospital.

I have also previously tried to locate the various asylums in and around Glasgow, many of which evolved into large psychiatric hospitals. The majority of these are now either partially or completely closed. This includes Gartnavel Royal, Woodilee Hospital, Gartloch Hospital, Leverndale Hospital, Dykebar Hospital and Lennox Castle Hospital. For information and photographs of what still stands from these hospitals see here.

On a look around Ruchill here, I looked at the former site of Ruchill Hospital, which closed in 1998.

So despite the long list above, there still remains a substantial number of disappearing and disappeared hospitals in Glasgow. Many people will remember having surgery, giving birth, working or visiting in these places. So in late 2017, here is a quick run round the hospital sites, to see what was still standing.

The rest...

The Western Infirmary

It served as a teaching hospital from its opening in 1874, at that time with 150 beds, increased in 1881 to 350 beds, and to 660 beds in the early 1900s. I like an 1888 description of the hospital, which mentions the heating system. "The wards are warmed by open central fires, the grates being enclosed in casings into which air channels are led from the outer walls, fresh air at a comfortable temperature thus passing freely into the ward."

|

| Plans for the Western Infirmary construction |

As well as increasing the number of beds at the hospital over the years, other facilities were built or acquired. In 1893 the hospital took over the "Lady Hozier Convalescent Home", on the site of a former army barracks in Lanark. The Tennant Institute of Ophthalmology opened in 1936 (the building on Church Street still standing) and the Gardner Institute of Medicine opened in 1938 (also on Church Street). The Western Infirmary building at that time was a grand sandstone building, but by the 1950s it was decided that the maintenance costs of the building were unsustainable.

|

| Western Infirmary, Glasgow in the 1900s |

Phase 1 of a re-building program was completed in 1974, whilst some care continued in the remaining older wards on the site. Phase 2 never happened, as with the building of the 576 bed Gartnavel General Hospital the two hospital sites worked as one unit. The concrete building erected in 1974 was designed with 256 beds. Before its recent closure, the Western Infirmary had 493 in-patient beds.

|

| Western Infirmary 100 years later (and uglier) |

With re-structuring of hospital provision in Glasgow over recent years, the Western Infirmary finally closed in Autumn 2015. This was facilitated by some expansion of services at the Gartnavel site (particularly the move of the Beatson Oncology services), and the building of the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital on the site of the former Southern General Hospital. This hospital has 1677 in-patient beds, with 256 children's beds in the adjacent Royal Hospital for Children.

The fact that the university had built the Western Infirmary on its land in the 1870s meant that, when somebody looked out the old contracts, the university was found to be entitled to reclaim the land. They are now marching ahead with their plans to redevelop the site with new university facilities. This has meant the sorry spectacle over recent weeks of watching the place where so many thousands of people were treated over the years being reduced to dust.

Rottenrow (Glasgow Royal Maternity Hospital)

One area where there have been dramatic changes in the provision of care is in maternity and gynaecology services. All in-patient maternity care in Glasgow is now either at the Princess Royal Maternity building at Glasgow Royal Infirmary, or at the wards in the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital. The advantage is that when things go wrong, childbirth is now happening on the site of a general hospital with all the emergency medical, surgical and ITU care that goes along with that. The disadvantage is the distances people now have to travel whilst in labour. (On a side note, is any other city in the UK as obsessed as Glasgow with giving every possible hospital a royal tag?)

For over a century, the hill that many a Glaswegian mother-to-be had to labour up, was Montrose Street, to get to Rottenrow. Glasgow Royal Maternity Hospital, to give it its proper name, opened on Rottenrow in 1881. The earliest hospital services for Glasgow's pregnant women were set up in 1792, as the curiously named "Glasgow Lying-In Hospital", which was closed by magistrates shortly afterwards. In 1834 a meeting held in the Town Hall set out the reasons for re-establishing a "lying-in" hospital.

|

| The Medical Institutes of Glasgow, a Handbook. 1888 |

The new hospital opened in 1834, in a garret of the Old Grammar School, Greyfriars Wynd. The first year of the hospital was disastrous, and highlighted the dangers to both mother and child, in childbirth at that time. One child died of erysipelas shortly after delivery, two mothers died of "inflammatory attacks incidental to the puerperal state" and a domestic servant at the hospital also died in the same outbreak, causing the hospital to be discretely closed and fumigated. One reason suggested in 1888 for the higher death rates at the Glasgow hospital, was that despite moral objections at the time, from the start they allowed unmarried woman to be admitted to the hospital, although only in an emergency situation. The contemporary doctors justified this at the time to unhappy contributors by saying "two lives were imperilled, one of which at least was an innocent one." Repeated outbreaks of disease threatened the hospital's future, and a lack of funds required cheaper accommodation.

In 1841 the hospital moved to St Andrew's Square, and greater numbers of women were able to deliver at the hospital. Increased student numbers brought extra income and in 1843 there were 176 confinements at the hospital. The hospital expanded, and in 1856-1857 there were 688 women who delivered at the hospital. "In all of these labours the forceps were used only three times."

|

| Glasgow Royal Maternity Hospital, Rottenrow, in the 1990s. |

As demand rose a new site was purchased, at the corner of North Portland Street and Rottenrow. In 1873 there were 312 deliveries at the hospital, resulting in the death of 8 women. Nearly 1000 other women that year were attended to by the staff within their own homes. With repeated problems of dry rot, and leaking sewage pipes in the building, it was pulled down and rebuilt in 1879, re-opening in 1881 as the Rottenrow hospital that stood for a century thereafter. In 1888 the world's first "modern Caesarian section" was performed at the hospital, and reports from that year proudly boast that "the mother and child are still alive and well".

|

| Glasgow's first three patients to undergo an anti-septic Caesarian section, all three of the women suffered from rickets |

Over the years new extensions and blocks were added to the tightly confined building, which resulted in a jumble of stairways and wards within it. Walking around the corridors it could feel as if M.C. Escher had designed the layout.

|

| Former entrance to Rottenrow Hospital |

In 2001, with the decision at the time to concentrate deliveries in hospital sites with wider emergency support, the hospital was closed and the patients transferred to the Glasgow Royal Infirmary site. The land was sold to Strathclyde University, who demolished the old hospital building, except for its entrance portal, and at present the land is used as a public, open space. George Wylie's giant sculpture of a nappy pin, "Maternity", the only reminder of the thousands of Glaswegians who took their first breath here.

|

| 1880 doorway into Glasgow Maternity Hospital on North Portland Street |

|

| Glasgow Royal Maternity Hospital entrance in 2017 |

|

| George Wylie's sculpture on the former site of Rottenrow Hospital |

|

| Rutherglen Maternity Hospital |

One of the shortest lived hospitals on this list is Rutherglen Maternity Hospital. In the 1960s a maternity unit was planned to sit alongside the Royal Samaritan Hospital, but when surveys found subsidence in the land a new site was sought. In 1967 land in Rutherglen was acquired, on Stonelaw Road, and Rutherglen Maternity Hospital opened in 1978. At the time it was felt to offer the most modern maternity facilities in and around Glasgow. Despite vehement local opposition, the hospital closed its doors on 1st August 1998. Over 56,000 babies had been delivered there in its 20 years of operation. I was working there when it closed, with a bagpiper on the roof on the last night. The site is now home to a health centre and care home.

Redlands Hospital

|

| Redlands House in the 1870s, surrounded by open fields |

Redlands Hospital in the west end of Glasgow was housed in a villa on Lancaster Crescent which had been built in 1870. It was where my brother was born in the 1970s and served as a maternity hospital until it closed in 1978. It is now again a private residence. In 1902 the Glasgow Women's Private Hospital was established, to provide treatment for women, by women doctors. It was initially established in Ashley Street in Woodlands (then called West Cumberland Street) before moving to 11 Lynedoch Place, in Park Circus, in 1915. Requiring larger premises Redlands House was bought in 1922, and after 2 years of renovations and extensions opened to its first patients in 1924. Until 1955 it was staffed entirely by women.

Royal Samaritan Hospital For Women

|

| Postcard of the Royal Samaritan Hospital for Women from about 1915 |

The Samaritan Hospital For Women opened in 1886 in Hutchesontown "for women of the poorer classes affected with serious diseases, more particularly those peculiar to their sex." Though initially only with three beds, it moved to larger premises, first in Kingston, and then 10 years after it first opened, to Coplaw Street. Several wards were added over time, and later a nurses' home on the Victoria Road side of the hospital. From 1907 it became known as the Royal Samaritan Hospital. It continued to provide in-patient and out-patient treatment to the women of the south-side of Glasgow until it was closed in 1991. At that time its patients were transferred (by me, among others, as I worked as a hospital porter at the Samaritan for a couple of years) to the gynaecology wards of the Victoria Infirmary up the road. The handsome buildings of the Royal Samaritan Hospital, where I used to walk the corridors delivering the mail and the meals, and collecting the samples and rubbish, have been converted into apartments.

|

| Royal Samaritan Hospital building in 2017, now converted into flats. |

Sick Children's Hospital

|

| The former Hospital for Sick Children, Scott Street |

|

| Plans for the Sick Children's Hospital Dispensary |

In 1914, requiring much larger accommodation, the Hospital for Sick Children moved to the Yorkhill area, with a new building on the former site of Yorkhill House. After being opened by the King and Queen it became the Royal Hospital for Sick Children. When faults were found in the concrete and steel of the building in 1965, it was closed down and Oakbank Hospital near Possil used for a few years, until the new Yorkhill Hospital was re-opened in 1971. The children's hospital here has now transferred to the southside, with some physiotherapy and orthopaedic clinics rattling about in the old building.

|

| Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow. 1955 |

|

| The 1970s Yorkhill Hospital, oink glass catching the morning sun |

By this time, Yorkhill was also the site of the Queen Mother's Maternity Hospital, built in 1964, and better known as "The Queen Mum's". This continued to be the place to deliver your west end babies until its closure in stages from 2006, and then finally in 2010.

|

| The (now closed) Queen Mother's Hospital, November 2017 |

Blawarthill Hospital

I cycled past Blawarthill Hospital recently, another place I used to work, to find all the land it once occupied being cleared. Again I want to deny any responsibility for the closure of this hospital. It was built at the junction of Holehouse Road and Dyke Road in Knightswood in 1897. At that time it was the Renfrew and Clydebank Joint Hospital for Infectious Diseases. The hospital had separate pavilions, which were added to over the years, with a villa style administrative block at the entrance (the only building still standing). In the 1960s it was converted into a geriatrics unit, with the construction of a day unit and other blocks over the years. The hospital remained open, with long term care wards, until 2012. Several of the buildings were destroyed in a fire in 2015, but the site will soon have homes, being built by Yoker Housing Association, and a planned social work care home.

|

| Blawarthill Hospital, November 2017 |

Drumchapel Hospital

|

| Sick Children's Hospital, Drumchapel, in its heyday |

Continuing around the former geriatrics units of the west end of Glasgow we come to Drumchapel Hospital. This large site off of Drumchapel Road, near the train station, was initially home to a children's hospital. Built in 1901 as a "Country Branch of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children" it was designed for patients with chronic conditions. It re-opened in 1930 after being extended to seven wards, with a nurses' home and administrative blocks added. In 1941 the hospital was damaged by German bombing, and patients transferred temporarily to Lennox Castle Hospital.

|

| Drumchapel Hospital geriatric wards in 2017, now all boarded up. |

In 1966 a 120-bed geriatrics unit was built alongside the original sandstone hospital buildings. Over time this evolved into the stroke rehabilitation wards for the Western Infirmary. The children's unit closed in the 1980s, and these old hospital wards were used as sets for some episodes of the TV series Cardiac Arrest whilst I was working here. The old hospital was finally demolished in the late 1990s. Several care homes now cover most of the former site, with the 1960s geriatric hospital still up for sale if you fancy buying it.

Knightswood Hospital is another old hospital which was founded as a fever hospital. The Joint Infectious Diseases Hospital for the Burghs of Maryhill, Hillhead and Partick was built in 1877. In 1888 it is described as having "two wards with pavilions for the different fevers...and a new pavilion, quite separate from the others...for cases of small-pox". At that time there were 100 beds, looked after by a resident medical superintendent, and the matron with four to six nurses under her.

Over time it was expanded, and by 1938 had 200 beds, in nine pavilions. In the 1960s it was providing a variety of medical beds for the Western Infirmary, and in 1971 a geriatric day unit was built. In the early 1980s when I was at school across the road from here at Knightswood Secondary, I used to come in one afternoon a week to pass out tea and biscuits, and chat to some of the long term residents (it was a school thing, we didn't do the organised Duke of Edinburgh awards stuff back then). The jumble of buildings on the site in the 1980s and 1990s was housing only patients under the care of the geriatricians by that time, and the hospital closed in March 2000. The site was quickly cleared and an extensive housing development built soon after within the old hospital walls.

|

| Entrance to the former Knightswood Hospital |

|

| Some of the housing on the site of Knightswood Hospital |

Belvidere Hospital

In the east end of Glasgow another former infectious diseases hospital later became a geriatrics hospital. Belvidere Hospital on London Road, close to Celtic Park, opened in 1870. A year later a separate smallpox hospital was built at the site. Numerous brick built, one storey pavilions on the site gave this hospital a very distinctive appearance.

|

| Belvidere Hospital in the 1990s |

The administrative block, where the nurses' homes were also accommodated, was a more traditional sandstone building, and this survived (in ruin eventually) as a listed building until 2014 when it made way for a new housing development on the site.

|

| Belvidere Hospital admin block, shortly before demolition |

In the early twentieth century the Belvidere infectious diseases hospital was called into action to combat an outbreak of bubonic plague in Glasgow. In August 1900 the first case, a docker, was discovered in the Gorbals. This later led to forty-eight cases and sixteen deaths, all blamed on an infected rat brought into the city on a ship. The outbreak was quickly contained, and news suppressed to prevent panic.

The Victoria Infirmary

With large general hospitals, or infirmaries, at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary and the Western Infirmary on the north of the river, it was felt that the population of the southside of Glasgow also required a similar facility. In 1888 work began on what would be known as the Victoria Infirmary. The plot of land used was an awkward one, triangular in shape, and on a hill. It was designed to be built in phases, with an administrative block at the top of the hill, facing Queen's Park. The wards were built in large pavilions down the hill behind this, in phases over several years as finances permitted and demand required.

|

| 1888 plan of the finished Victoria Infirmary building, looking southwards |

As with the other hospitals above, as medical treatment changed, the physical buildings were adapted to accommodate new innovations. X-ray facilities and operating theatres were added, laboratory facilities, a laundry and nurses' homes. The distinctive day rooms and balconies of the Victoria Infirmary, overlooking Battlefield Road, were added in 1911. In the 1920s Philipshill Hospital in East Kilbride, which operated largely as an orthopaedic unit (initially called the Victoria Auxilliary Unit) was built. It is also now closed, the last patients being moved out in 1993. The only part of the hospital (which I remember visiting as a student) still standing is the hospital chapel, recently for sale for £50,000 if you fancy a wee renovation project.

In the 1960s the nearby Victoria Infirmary Geriatric Unit, or Manshionhouse Unit, was constructed, a 250-bed geriatric hospital and day unit.

|

| OS maps from 1894 and from 1938 showing the gradual expansion of the Victoria Infirmary (from NLS website) |

I was aware that the Sanctuary Group had received permission to redevelop the Victoria Infirmary site for housing, but when I went to have a look at the old hospital recently I was amazed to see how much of the old hospital they have already flattened. In effect it looks like they will only be keeping the old administrative block, and the three large ward pavilions. The ancillary units and link corridors between them are already all but flattened, and the A+E block and out-patients units at the bottom of the hill, beside Battlefield Rest, are currently being demolished. There have been some understandable local complaints about the scale of the new development, and how sustainable any new traffic issues will be. However, for the developers it is full steam ahead.

Miscellany Part 1. Glasgow Eye Infirmary

There are of course many other hospitals in Glasgow which are now gone, which I have not written about here, or in previous blogposts. Others still have the threat of closure hanging over them, such as Lightburn Hospital. A quick mention to two which were before my time, but left a lasting impression, for different reasons. The Glasgow Eye Infirmary I mention because the building still stands, in Sandyford Place, with its eye-catching (sorry) golden mosaic sign. The terrace of houses here were not the original home to the Eye Infirmary, which first opened on North Albion Street in 1824. Over time it moved to different city centre sites, including David Dale's former villa on Charlotte Street in the 1850s. In the 1870s it moved to a 70 bed, purpose built unit in Berkley Street. Premises in Sandyford Place were purchased first in 1928 for nurses's homes and out-patient facilities. In the 1930s more addresses in the terrace were purchased and this became the new home of the Glasgow Eye Infirmary.

|

| The Glasgow Eye Infirmary, with the dome of the local gurdwara behind it |

The Sandyford Clinic is now based in this building. For many years this has been known as the home of Glasgow's sexual health services, but it still bears the distinctive banner of the old hospital.

Miscellany Part 2. Lock Hospital

On the theme of sexual health, it is also worth noting Glasgow's original hospital for the treatment of venereal diseases. This takes us back up to Rottenrow. The Lock Hospital was founded here, at 151 Rottenrow Lane in 1805, with 11 beds. Of note, at the time it was for "the treatment of unfortunate females."

Although Lock Hospital sounds like a prison, the name is thought to derive from the French word loque, a bandage used for lepers. Early prejudices about venereal disease thought of women as the carriers of it, syphilis in particular being the problem at that time. A large number of patients cared for in the city's asylums in the 19th century were those suffering from the disturbing end-stages of syphilis.

The Lock Hospital re-located eastwards to 41 Rottenrow in 1845, and expanded to 7 wards with room for 80 beds if required. An 1857 map shows that at this time it lay between a gasometer and "Purefying House" on one side, and an "Asylum for Indigent Old Men" and an "Industrial and Reformatory School" on the other.

A report from 1882 makes for interesting reading. In this report the author reflects on the effects the "Contagious Diseases Acts" have had on the hospital. These laws were a response to the number of soldiers in the British Army succumbing to venereal diseases. Women were the target of the laws, men presumably the helpless victims who needed no treatment. It gave police the right to arrest anyone suspected of being a prostitute, compulsorily examine them for signs of venereal disease and confine them to a Lock Hospital for treatment if required. The report found less women being treated after the act was passed, and speculated that the incidence of "neither vice nor disease" had reduced in Glasgow, but prostitutes were having to work clandestinely and not coming for treatment. The report also records the occupation of those women admitted to the hospital for treatment over the previous decade, a diverse range of Victorian trades, including one rivetter.

|

| Occupations of women admitted to the Glasgow Lock Hospital 1870-1880 |

In 1888 the Lock Hospital is described as admitting 330 patients annually, and "many of them being very young girls". This 1888 document makes no explanation of how these young girls were being infected. In puritanical Victorian Britain, one Lock Hospital surgeon bizarrely recorded that a seven year old girl had "given the illness to herself". It is clear that the horrors of child abuse, are sadly not a new phenomenon.

Most of the patients were treated with mercury, popular at the time, but toxic. Many women entering the hospital were not allowed to leave until after their treatment. Others with more advanced disease, or suffering mercury toxicity would move onto one of the nearby asylums. An average stay is described as being for 29 nights. By the early 20th century the hospital was still in operation, with 42 beds. As treatments improved with the invention of antibiotics, new centres for the treatment of venereal diseases opened, although the Lock Hospital was still in operation in the early 1940s. The building was demolished in 1955.

This article from the 1914 British Journal of Nursing describes the treatments patients could receive in the Glasgow Lock Hospital at that time.

|

| Glasgow Lock Hospital, Rottenrow, prior to its demolition in the 1950s |

Summary

There are many reasons behind the changing provision of health services.Disease prevalences change, treatments and investigations change. We no longer need huge remote hospitals for infectious diseases, whereas childbirth in hospital is now the norm. Until recently the NHS provided long term care for the infirm elderly in long stay geriatric wards, but political decisions in the 1980s and changing demographics moved this care into the private sector. The building of a huge new hospital in Glasgow has centralised care that was previously carried out on several sites and this has led to the current wave of demolitions. However hospitals are more than bricks and mortar and are tied to important memories for many people; births, deaths and life changing events. Beyond that, thousands of people worked in these places all their days, so I hope to have stirred a few memories before the bulldozers finish their work.